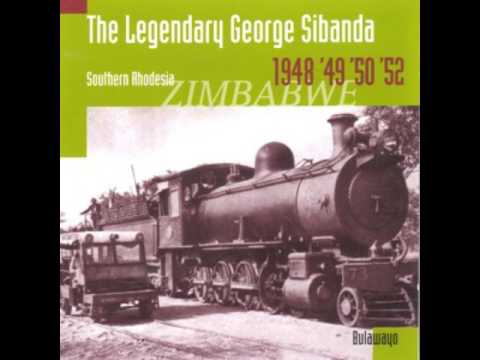

Here’s a story about how a folk song from Bulawayo became a cult classic in America.

Sometime in the 1940s, there was a dude called George Sibanda, plying the bars and halls of Bulawayo with his acoustic guitar.

There was also a fellow called Hugh Tracey, a famous ethnomusicologist.

(The term “ethnomusicologist”, by the way, is white-folk speak for white guy who claims to discover black folk music, eminent saviours of ‘ethnic music’. But that’s another whole debate).

Tracey had been prowling these shores for music since the 1920s. His biggest “discovery” was August Musarurwa’s world famous “Chikokiyana”, or Skokiaan.

Now, 1940s Bulawayo was quite a scene. Many young men and women were moving there from around the country, seeking jobs in the booming factories. Naturally, the music scene was vibing. Among the budding stars was George Sibanda, and his guitar.

Around the time, Gallo Records, a major recording company in South Africa, was looking for new sounds to record. That’s how the likes of Sibanda and other contemporaries such as Josaya Hadebe and Sabelo Mathe got their break.

By some accounts, George’s first recording with Tracey, the children’s folk song Gwabi Gwabi, is the first commercial recording in this country. It was not until 1959 that a commercial recording company set up shop, with the opening of Teal Records (what we today know as Gramma).

Gwabi Gwabi was recorded and released in 1948 under the Decca label, as part of Tracey’s Music of Africa series. And that’s how its crossover story started. The record was reissued in Europe in the ‘50s, re-released on a 12-inch by Gallo in SA in the ‘60s, and issued yet again in the early ‘70s. It was that good.

Gwabi gwabi kuzwa ngile ntombi yami ihlal’ enkambeni shu’ ngiyamthanda

Ngizamthengel’ amabhanzi iziwiji lebanana

In the ‘60s, an American folk singer laid his hands on Music of Africa. The guitar-plucking and infectious voice of George of Bulawayo were obviously too hard to resist. Soon, the record was being played by guitarists in the unlikeliest of places in America; redneck bars where struggling country and folk singers were used to playing songs about poor harvests and cattle.

Soon, there was something of a scramble to record Gwabi Gwabi among folk singers. The track was soon on a musical review, Wait a Minim, and was recorded by dozens of folk singers, among them singers with names such as Ramblin’Joe Elliot, Taj Mahal and Arlo Guthrie.

It gets weird.

For some reason, Decca had released the song in the West as “Guabi Guabi”, and not Gwabi Gwabi. Also, Arlo Guthrie, one of the folk singers, decided that “gwabi gwabi” was a name, “Guabi”.

Guthrie had decided it wasn’t enough just to sing the song. It had to have an exotic story to it, you see. So he made up tales. The song, he would tell his audiences as he performed the song across America, was about a thief called “Guabi” who slipped on a banana and fell out of the window of a police station.

Early in 2017, I came across a video of Arlo Guthrie performing the track somewhere in America. He told the story of how a bunch of African musicians had stood in awe when he sang them this old Ndebele song. Knowing nothing about his career, they encouraged him to take up music for a living!

Gwabi Gwabi was a major hit for Arlo Guthrie.

But for George, it had been a starkly different tale. He did find some fame, playing to audiences all across Southern Africa. His fame had gone beyond the region; he had fans as far afield as Kenya.

George recorded 15 tracks, according to Joyce Jenje Makwenda in her must-read book,Zimbabwe Township Music.

That music was recorded in the ‘40s, a time many local crooners were aping American music (sleek dark suits, hair gel and Stetson shoes a la Nat King Cole and the like). But for George, his style was “not directly imitative of American and other foreign models”, according to an account by Thomas Turino in his book Nationalists, Cosmopolitans, and Popular Music in Zimbabwe.

But Sibanda got precious little for his pioneering efforts.

According to one article: “The lyrics of the album tell stories of the industrialization of the cities of southern Africa in the middle of the last century, of train stations and airplanes, of hip urban gangsters in their fancy dress, of rowdy nights in segregated bars and of young men struggling to collect the cattle needed to pay the bride price to marry their hometown sweethearts.”

Nobody knows exactly when the legendary George Sibanda died. Several accounts say he died of alcohol poisoning sometime in the 1950s.

To this day, in many small-town bars in America, they still play Gwabi Gwabi. At home, even among those that grew up singing the song as kids, few have ever heard of the legend of George Sibanda, the pioneering guitarist from Bulawayo.